Cheers,

A few weeks ago some of us went mudlarking along the Thames at low tide. Here is more than you probably want to know about mudlarks, mudlarking and clay pipes.

Ru

PS Hope any of you having to deal with the big winter storms are staying safe and warm.

|

My mudlarking finds : note the small plastic glass with the collection of pipe stems. I may make wind chimes. http://www.amelia-parker.com/p/clay-pipes-history.html products made from found clay pipes |

|

We call it beach combing at home; here it’s mudlarking. One Sunday morning Sue and Ed Kelly, Sue Ross and I put on our boots, and older clothes, and went off to try our hand at mudlarking. One can get a permit for real intensive searching, but we were just out for fun and hopefully an intact clay pipe. Metal Detecting and Digging on the Thames Foreshore “Thames Foreshore Access for Leisure or Pleasure including Metal Detecting and Digging The Thames foreshore is potentially hazardous and some dangers may not always be immediately apparent. The Thames rises and falls by over 7.0m twice a day as the tide comes in and out. The current is fast and the water is cold. Anyone going on the foreshore does so entirely at their own risk and must take personal responsibility for their safety and that of anyone with them. In addition to the tide and current mentioned above there are other less obvious hazards, for example raw sewage, broken glass, hypodermic needles and wash from vessels. Steps and stairs down to the foreshore can be slippery and dangerous and are not always maintained. Before going onto the foreshore consider: • sensible footwear and gloves • carrying a mobile phone • not going alone • the tide; is it rising or falling? Always make sure you can get off the foreshore quickly – watch the tide and make sure that steps or stairs are close by. Finally, be aware of the possibility of Weil’s Disease, spread by rats urine in the water. Infection is usually through cuts in the skin or through eyes, mouth or nose. Medical advice should be sought immediately if ill effects are experienced after visiting the foreshore, particularly “flu like” symptoms ie temperature, aching etc. Metal Detecting and Digging Anyone wishing to carry out metal detecting or digging/scraping on the Thames foreshore requires a permit from the Port of London Authority. Walking on the Thames foreshore does not require a permit.” http://www.npr.org/ talks about the conflict between “mudlarks” and archaeologists. |

|

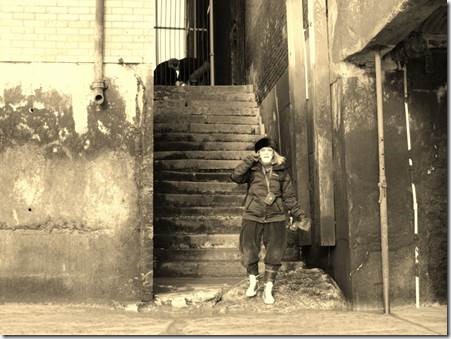

Sue Ross coming down the stairs at New Crane Wharf We were all bundled up for the cold, but the bright sun and lack of wind had us much too warm right away. |

|

Sue Ross with her red rubber gloves and matching bag! We did look like bag people |

|

Ed and Sue Kelly; Sue wore her Wellies, Ed wore giant plastic bags over his shoes. |

|

Our main goal was to find at least one intact clay pipe. Not an easy thing to do as they are several hundred years old in many cases. We all found bits and pieces and Ed found a partial pipe stem with a bowl. I found stems and bowls, two with markings! |

|

Leaf design on the bowl |

|

The Tappin family: tobacco pipe makers of Puddle Dock Hill, Blackfriars, in the City of London Some London pipe makers produced rare decorated bowls incorporating heraldic art at this time and leaf or barley patterns were commonly used to cover seams on the bowl, as shown in Photo 5 below. http://www.kieronheard.com/pipes/tappin.htm Photo 5. Leaf or branch design on pipe bowl seam to cover up any misalignment in the mould halves. Website photo |

|

Pipe makers’s initials G on one side and W on the other on a fragment that I found White ball clay pipe One bowl has the letters W.G. stamped on the rear of the bowl instead of T.D. It also has a “W” on the left side of the heel and a “G” on the right side. The W.G. versions, according to Walker (1972:37), “are possibly slightly later than the others – their earliest occurrence appears to be on American Revolutionary War sites – but they are perhaps the most common, and in derived forms certainly the longest lasting”. Walker also reports that the W.G. version “continued with steadily – degenerating decorative motifs to ca. 1830” (1972:37). Office of History and Archaeology – words State of Alaska > Natural Resources > Parks and Outdoor Recreation > History and Archaeology Castle Hill Archaeological Project http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/oha/castlehill/pdfdocuments/chapter10.pdf |

|

Evolution of clay tobacco pipes in England Shortly after 1700, pipes changed in quality, being more accurately made, with a smoother finish and with thinner walls and slender stems. The top of the rim was now trimmed parallel to the stem, as shown in Photo 4. This also shows the maker’s letter W on the side of the heel. Post-1700 pipe with the bowl rim trimmed parallel to the pipe stem. Note the letter W on the heel, this denotes the maker’s surname began with W. On the left hand side of the heel is the letter I (often used in place of J) representing the Christian name. http://www.cafg.net/docs/articles/claypipes.pdf website photo |

|

Now mudlarking is a hobby. Once upon a time children were sent out to search for anything that could be sold or used. http://www.mydoramac.com/wordpress/?p=19045 our visit to the Museum of London where I first read about mudlark children. http://spitalfieldslife.com/2010/09/29/the-life-of-a-mudlark-1861/ good information always on the Spitalfields Life site. And then I got carried away as I often do and came across a Sir Laurenc Oliver film about a Mudlark. You can watch it online. |

|

The Mudlark 1950 film When Wheeler, a young orphan who survives as a scavenger on the mudflats of the River Thames in late nineteenth-century England, comes upon a dead man, he steals his small cameo plaque of Queen Victoria although he does not know who she is. Two other urchins try to take the cameo away from "The Mudlark" but are stopped by a night watchman, who tells him about the Queen, who is known as "The Mother of England." The night watchman also mentions that she has lived in seclusion in Windsor Castle since the death of her husband, Prince Albert, fifteen years earlier, and Wheeler, intrigued by the Queen’s motherly appearance, makes his way to Windsor Castle to try to see her. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli has come to visit Victoria and tells John Brown, Prince Albert’s former servant and now confidant of the Queen, of his concern about her continued seclusion. In an audience with the Queen, Disraeli informs her that the passage of an important reform program is being vigorously opposed and needs her total support and that her seclusion is creating a very negative impression. Disraeli advises her to accept an invitation to attend the one hundreth anniversary celebration of the Lambeth Foundling Hospital. However, Victoria does not wish to leave Windsor, even for a brief period, as it holds such fond memories of her late husband. Meanwhile, Wheeler enters the castle grounds, falls down a coal shute and finds his way into the Queen’s private chambers. Emily Prior, the Queen’s Maid of Honor, is romantically involved with Guards officer Lt. Charles McHatten, but her mother, Lady Margaret Prior, does not approve of the match due to Charles’s low social standing. Charles has sought permission from Lady Margaret and the Queen to marry Emily but both forbid Emily to see Charles again. Emily responds that she will marry whom she wishes and that the Queen can no longer control her life. Wheeler, meanwhile, is discovered in the Queen’s dining room by maid Kate Noonan and footman Slattery, an Irishman who tries to impress Kate by saying he is plotting against the monarchy. They hide Wheeler behind some curtains as the Queen, Disraeli and other dinner guests enter. During the dinner, Wheeler falls asleep and his snoring causes him to be discovered. As there have already been several attempts on the Queen’s life, he is regarded with great suspicion. Wheeler reveals that he has overhead Slattery saying that he wanted to burn down the castle. Brown interrogates the boy but, realizing he is starving, orders him to be fed, even instructing him on the proper use of a fork. Meanwhile, Emily, who has decided to elope, leaves a note for her mother and goes to meet Charles. However, he is Officer of the Day and is summoned to question Wheeler, leaving Emily waiting in the rain. Brown, a Scot with a fondness for the national drink, takes a liking to the boy and gives him a tour of the castle, even permitting him to sit on the Queen’s throne. However, they are discovered by Charles, and Wheeler is handed over to the police as a potential assassin and is held prisoner in the Tower of London. The Queen orders Disraeli to have the case against the boy handled with great caution and with as little public comment as possible as there is speculation that Wheeler might be part of an Irish plot. A police officer rounds up some of the cronies and fellow scavengers Wheeler thinks could testify to his character, but they claim not to recognize him. Meanwhile, Emily and Charles have planned another elopement rendezvous, but this time he is summoned to see Disraeli and Emily is left waiting once again. Later, after the Queen indicates to Emily that her position on the marriage might be changing, Emily and Charles finally keep a rendezvous. In the House of Commons, Devoy, an Irish Member, denounces the newspaper characterizations of Irish involvement in the Wheeler case. Disraeli agrees that Wheeler acted alone and uses the boy’s life story in his campaign for major social reforms, which gain overwhelming support from the Members. Later, Disraeli tells Wheeler that the government has arranged for his care and schooling. Displeased by a rebuke in Disraeli’s speech, the Queen summons him to Windsor. The prime minister tells her that although she may not approve of his method, his campaign has been successful. He then offers to resign. Brown defuses the situation by interjecting that Victoria’s late husband would have approved of Disraeli’s actions. Wheeler has sneaked into the castle again, and Brown presents him to the Queen, who tells him that he is a very naughty boy. He touches her heart, however, when he shows her the cameo he has saved and says that he only wanted to see her. The Queen thanks him and instructs Disraeli to watch over him. Later, Queen Victoria ends her seclusion and appears at the hospital’s celebration where she is, once more, greeted with affection by her subjects. http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/84107/The-Mudlark/ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22AXes2f_s4 Part one of the Mudlark http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0w2Rdz8iDT0 Part two of the Mudlark |

|

A future treasure we left behind |

|

My gloves started to fall apart I guess from a mixture of Thames River water and whatever cleaning fluid I’d used the gloves with previously. Luckily I’d gotten a Tetanus booster while we were home in October. |

|

Ed trying to unwrap himself at the end of our mudlarking. |

|

Leave behind only footprints! |

|

S E R WHITE & is all I know. There’s a W on the bottom. So far no luck finding any info. I may try a grocery store or pub and ask them. |

|

Possibly a bottle topper with a teardrop shpe inside. |

|

It reminds me of those blue ceramic chickens! |

Clay tobacco pipes and smoking in London

Tobacco plants from the New World were first cultivated in Europe as early as the middle of the 16th century, when they were prized for their exotic appearance and supposed medicinal properties when taken in the form of snuff. The earliest account of a pipe being used to smoke dried tobacco leaves comes from England and dates the introduction of the practice to the 1570s. English adventurers exploring the eastern seaboard of North America in the age of Elizabeth I had encountered native peoples smoking dried tobacco in pipe-like instruments made from clay. Unsurprisingly, they introduced the habit to their home country, where it quickly became both fashionable and popular. By the end of the 16th century, smoking had become widespread in England and a pipemaking industry was growing rapidly to meet the ever-increasing demand. The earliest pipes were handmade, but by the end of the 16th century, the use of moulds greatly increased productivity and efficiency of manufacture.

At first London was the focus of this new industry, although from the mid 17th century onwards more and more centres around the country began to make clay tobacco pipes, each developing their own individual variations on the basic form. In 1619 the Charter of Incorporation of the Tobacco Pipemakers of Westminster was signed by 36 individuals, representing more than half of the 62 pipemakers recorded in London at this date. Pipes made by some of these men are illustrated here. A new Charter of Incorporation was granted in 1634 and signed by 22 pipemakers at a time when the industry was beginning to expand increasingly to other regions outside the capital. In 1663 the company was reconstituted by a new charter and reorganised as a City Company without livery. These major developments in the growth of the pipemaking industry during the 17th century provide the background to a major project undertaken by MoLAS, with generous funding by the City of London Archaeological Trust (CoLAT), to create and make available to the public and researchers a database of marked clay pipes found in London excavations. http://archive.museumoflondon.org.uk/claypipes/pages/claypipesinLondon.asp

Clay pipes and the archaeologist

One of the most valuable features of clay pipes, from an archaeological perspective, is the fact that they can be closely dated. Improvements in technology, the rapid growth of the tobacco trade with the New World, bringing down prices, fashion and taste all worked together to bring about progressive developments in the shape and size of the clay pipe bowl. In 1969 David Atkinson and Adrian Oswald published a typology of London clay tobacco pipes, based on the association of dated groups of finds excavated by the Guildhall Museum and identified pipemakers. Changes and variations in form were charted at roughly 30-year intervals, providing an invaluable guide to dating that remains the basis of present clay pipe studies in London.

Since clay pipes were essentially disposable items, universally and easily obtainable and thrown away after only a few smokes, their potential for dating archaeological deposits is considerable. They do, however, have an importance that goes far beyond chronology, throwing light on the role and history of leisure and recreation in daily life, furthering our understanding of the place of smoking in society, and the organisation of the industry across the country. Their study can contribute to the comparison of regional economies within the London area, trade and contact with other regions, as well as with the Continent and North America. For these reasons excavated pipe assemblages from London are recorded in some detail, and not only on form and date. The data are stored in the MoLAS relational database and have been used in the creation of this web page. These routinely record the presence and extent of milling and burnishing, as indicators of quality, as well as decoration, which became increasingly popular from the later 18th century onwards.

From early on in the life of the industry tobacco pipemakers marked their pipes with their initials or with a symbol such as a fleur-de-lys or a wheel. The majority of pipes were not marked, but those that are give valuable clues to date and area of manufacture when they can be related to documented pipemakers. This is by no means always possible, especially with common combinations of initials and with symbols. Nonetheless, many London pipes have been identified as the work of known pipemakers with varying degrees of certainty and a picture of their distribution and the organisation of the industry has begun to emerge.

http://archive.museumoflondon.org.uk/

http://scpr.co/index.html Society for Clay Pipe Research