Cheers,

For someone who lives on a boat, I truly have no real interest in them or naval history. Or military history in general though I am beginning to wonder how we won the Revolutionary War given the great British Navy. Lots of thanks to the French and Spanish I think. Sometimes I wonder if the British lost us or just decided to jettison the whole lot of us pesky Yankee Doodles.

This email is about the HMS Victory because she’s the reason Randal wanted to visit Portsmouth….I went along to keep him company. The more “interesting stuff” will be in the following emails.

Ru

Portsmouth Historic Dockyards

http://www.historicdockyard.co.uk/

Often when visiting places I take a zillion photos, return home, do tons of research and then send out overly long emails. Well, I must admit that British Naval History just isn’t one of my interests. I spent two full days touring ( more like following along behind Randal) the Portsmouth Historic Dockyards and that’s about enough of that. The odder quirky things caught my attention, but the real focus, ships and battles didn’t. Sorry, that’s just the way it is. There’s lots of good information at your local library for anyone who wants to know more. Tell them I sent you.

|

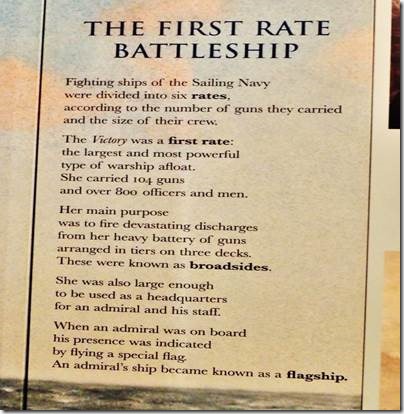

Nautical terms we use in our everyday language, “first rate” and “broadsides.” What is the difference between a broadsheet, broadside and tabloid? A broadsheet is a full-size newspaper, sometimes mistakenly called a broadside. A broadside is a a large sheet of paper, generally printed on one side and folded into a smaller size, often used as a direct-mail piece or for door-to-door distribution. A tabloid is a newspaper of less-than-standard size, generally about 1,000 – 2,000 AGATE lines on a page that is 14 inches high and has four or more columns, about 12 inches in width. |

|

HMS Victory…… “On 7th May 1765 HMS Victory was floated out of the Old Single Dock in Chatham’s Royal Dockyard. In the years to come, over an unusually long service, she would gain renown leading fleets in the American War of Independence, (against us) the French Revolutionary War (against the French) and the Napoleonic War. In 1805 she achieved lasting fame as the flagship of Vice-Admiral Nelson in Britain’s greatest naval victory, the defeat of the French and Spanish at the Battle of Trafalgar. For Victory, however, active service did not end with the loss of Nelson. In 1808 she was recommissioned to lead the fleet in the Baltic, but four years later she was no longer needed in this role, and she was relegated to harbour service – serving as a residence, flagship and tender providing accommodation. In 1922 she was saved for the nation and placed permanently into dry dock where she remains today, visited by 25 million visitors as a museum of the sailing navy and the oldest commissioned warship in the world. Over a period of 34 years, between 1778 and 1812, HMS Victory took part in five naval battles. Trafalgar is not only the most famous of these but also the last. Commissioned for service in the American War of Independence, Victory fought in the First and Second Battles of Ushant and the Battle of Cape Spartel, whilst during the French revolutionary War she was Admiral Jervis’ flagship at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. “ http://www.hms-victory.com/history Randal looking at the model od HMS Victory with its full masts. |

|

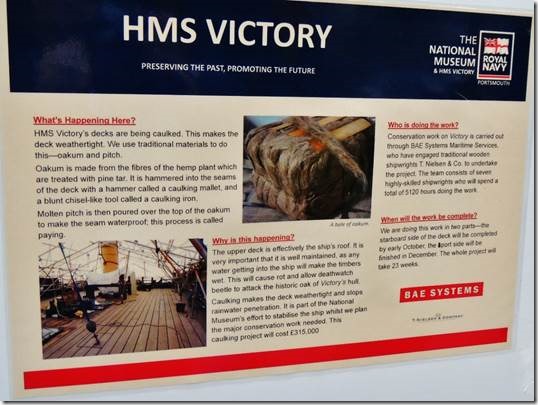

The top half of the masts are being repaired. (No she’s not leaning to the side, it’s just an odd photo.) “The final mast removal on HMS Victory has taken place this morning (0800 Friday 23rd September, 2011) when the mizzen top mast was removed as part of the restoration work taking place on Nelson’s flagship at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. Bell Rigging, sub-contractors for BAE Systems have been overseeing the work as the ship’s three masts, bowsprit and rigging have all been dismantled over the summer. The last time HMS Victory was seen without her top masts was back in 1944, so this really is a once in a life time opportunity to see HMS Victory under-going such extreme maintenance. The National Museum of the Royal Navy’s Director General, Professor Dominic Tweddle said: “Watching the team painstakingly disassemble the rigging and masts of HMS Victory has been heart stopping at times! To do this intricate work, while still keeping Victory open to the public, has been a logistical masterpiece. Interestingly, with her topmasts down, Victory will look much as she did after the Battle of Trafalgar when she had to be towed to Gibraltar for repairs.” Most of the highly skilled operation has been carried out by master shipwrights and other specialist staff employed by BAE Systems who, while operating on the cutting edge of technology on modern warships, maintain the age-old wooden shipbuilding skills. John O Sullivan, BAE Systems Project Manager for HMS Victory, is in charge of the maintenance: “We have removed the upper sections of all three masts and bowsprit, booms, yards and spars, including 26 miles of associated rigging and 768 wooden blocks, some of which are 100 years old. We will then catalogue and document everything for future surveying, design and replacement. When the rigging is replaced a decision will be made as to whether the wooden rope blocks can be re-used, recycled or replaced. Our team will carefully manage this major restoration project, keeping disruption to a minimum.” – See more at: http://www.historicdockyard.co.uk/ |

|

During our tour it was hard to hear over the pounding of the caulking. Randal did a second tour the following day and the hammers were silent. And each guide has their own story to tell so he enjoyed both tours. |

|

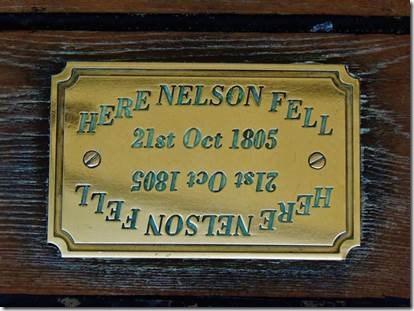

Lord Nelson: the hero of Trafalgar … his dress coats with empty sleeve as he’d lost his right arm in battles. He really is a huge hero in British Naval History. Our guide explained that the G R stood for George Rex….King George the III. He also pointed out to those Americans on the tour, that George III was our king too, albeit our only king. “About fifteen minutes past one o’clock, which was in the heat of the engagement, he was walking the middle of the quarter-deck with Captain Hardy, and in the act of turning near the hatchway with his face towards the stern of the Victory, when the fatal ball was fired from the enemy’s mizzen-top. . .” http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/lordnelson.htm |

|

Some of the guns |

|

Today springs are used to check recoil, but in the days of HMS Victory the cannon were on wheeled carriages, with ropes to stop them from recoiling too far when fired. Also, the ship pitched when sailing, especially in the rough seas, and the term "loose cannon" originally referred to a ship’s cannon loosed from its rope and rolling dangerously on the deck. http://www.go2gbo.com/ another good explanation ….but we didn’t….Oh well |

|

Sleeping quarters…and also you shroud if buried at sea. They would sew you into the cloth used for your bunk, the final stitch through your nose. “Burial at sea, a simple yet most impressive and dignified ceremony, is the most natural means of disposing of a body from a ship at sea. It is still the custom to sew the body into a hammock or other piece of canvass with heavy weights, formerly several cannonballs, at the feet to compensate the tendency of a partly decomposed body (as would be the case in the tropics) to float. To satisfy superstition, or to ensure that the body is actually dead, the last stitch of the sailmaker’s needle is through the nose. Ensigns of ships and establishments in the port area are of course half-masted during a funeral.” http://www.hmsrichmond.org/avast/customs.htm |

|

“HMS Invincible, a 74 gun ship, was wrecked in the Solent in 1758. In the late 1970’s the ship was excavated by archaeologists. This collection numbers over six hundred artefacts from the ship providing a unique picture of life onboard an eighteenth-century warship. This square plate was issued to a sailor for eating his food off. It is the origin of the expression ‘three square meals a day’. Ref: 1987.0045.01 INV 175 http://www.thedockyard.co.uk/ |

|

Letting the “cat out of the bag>” “A second theory ascribes the origin of the saying to the British Royal Navy, asserting the instrument of punishment used upon those errant in their duties or behaviors (a whip called the ‘cat of nine tails’ or ‘cat-o’-nine-tails’) was routinely kept in a red sack, thereby a sailor who brought to light the transgressions of another was "letting the cat out of the bag." However, no evidence documents that such whips were commonly stored in sacks, or that the phrase "let the cat out of the bag" was initially associated with maritime origins or usage. (but it is what our guide told us and you can see the red bag hanging there.)

Read more at http://www.snopes.com/l LAWS OF THE SEA AND PUNISHMENTS (not pleasant reading) “The punishment listed in the Admiralty Black Book for sleeping on watch, a very serious offence because it endangered the ship, was at first humiliating and for repeated offences brutal. A bucket of sea-water was poured over the head of a first offender. A second time the offender’s hands were tied over his head and a bucket of water was poured down each sleeve. For a third offence the man was tied to the mast with heavy gun chambers secured to his arms, and the captain could order as much additional pain to be inflicted as he wished. The fourth offence was inevitably fatal; the offender was slung in a covered basket hung below the bowsprit. Within this prison he had a loaf of bread, a mug of ale and a sharp knife. An armed sentry ensured that he did not return aboard if he managed to escape from the basket. Two alternatives remained — starve to death or cut himself adrift to drown in the sea. The Articles of War, a purely naval code of discipline, stem from this source. These were first written in 1661 in the reign of Charles II. The punishments listed were brutal, but the principle has remained to present times: "For the good of all, and to prevent unrest and confusion." The King’s Rules and Admiralty Instructions (K.R. & A.I.), which made their first appearance in 1731, contain general regulations, including discipline, governing the naval service. A punishment which was particularly harsh and usually fatal was keel-hauling, awarded for serious offences, and discontinued in the Royal Navy about 1720. It was still practised in the Dutch and French navies until 1750. Execution by hanging at the yardarm was the normal punishment for mutiny in the fleet. The last execution was carried out in 1860. As a capital punishment it was by no means instantaneous as is said to be with the case with our modern practice. The prisoner’s hands and feet were tied, and with the noose about his neck a dozen or so men, usually boats’ bowmen (the worst scoundrels in the ship) manned the whip and hoisted him to the block of an upper yard, to die there by slow strangulation. The most common type of punishment, inflicted for almost any crime at the discretion of the captain, was flogging with a cat-o’-nine-tails (1). This was carried out "according to the customs of the service", namely at the gangway. The indicted was given twenty-four hours in which to make his own cat. He was kept in leg-irons on the upper deck while awaiting his punishment. When the cat was made the boatswain cut out all but the best nine tails. If the task was not completed in time the punishment was increased. With heads uncovered to show respect for the law, the ship’s company heard read the Article of War the offender had contravened. The prisoner was then brought forward, asked if he had anything to say in mitigation of punishment, then removed his shirt and had his hands secured to the rigging or a grating above his head. At the order "Boatswain’s mate, do your duty" a sturdy seaman stepped forward with the cat — a short rope or wooden handle, often red in colour, to which was attached nine waxed cords of equal length, each with a small knot in the end. With this the man was lashed on the bare back with a full sweep of the arm. After each dozen lashes a fresh boatswain’s mate stepped forward to continue the punishment. Each blow of the cat tore back the skin and subsequent cuts bit right into the flesh so that after several dozen lashes had been inflicted the man’s back resembled raw meat. After each stroke the cords were drawn through the boatswain’s mates fingers to remove the clotting blood. Left-handed boatswain’s mates were especially popular with sadistic captains because they would cross the cuts and so mangle the flesh even more. After the man was cut down he was taken to the sick berth, there to have salt rubbed into his wounds. This was done not so much to increase the pain as for its antiseptic qualities. From 1750 into the 19th century twelve lashes were the maximum authorised for any one offence. Until the end of the 18th century the punishment for theft, a hateful crime against one man or many in a ship at sea, was for the thief to run the gauntlet (or gantlope). The offender first received a dozen lashes in the normal manner with a thieves’ cat, with knots throughout the length of the cords, and while still stripped to the waist passed through two lines of all the ship’s company, to be flogged with short lengths of rope. Lest he move too fast to benefit fully from this ordeal the master-at-arms marched backwards a pace ahead of him with the point of his cutlass against the thief’s chest. And to prevent him stopping a ship’s corporal followed him in a similar manner. On completion of the course the thief was given a further dozen lashes. Another form of punishment was flogging around the fleet. The offender was secured to an upright timber in a ship’s boat, and when it pulled alongside each gangway a boatswain’s mate entered the boat and inflicted a certain number of lashes. For added effect the boat was accompanied on its rounds of the fleet by other boats, each with a drummer in the bows beating a roll on his drum. Flogging was not abolished in the British forces until 1881 in response to strong public opinion. Until suppressed in 1811, it was a common practice for boatswains’ mates to carry and use on their men colts or starters, small whips somewhat like knouts or knotted ropes, which they carried concealed in their hats. The boatswain’s mark of authority was the bamboo cane or rattan he always carried, and with which he summarily executed punishment. A punishment awarded by messdeck court martial for cooks who spoiled a meal was to be cobbed and firked, that is beaten with stockings full of sand or bung staves of a cask. This practice was officially disallowed after 1811. A form of corporal punishment, i.e. "birching or caning on the bare breach" (K.R. & A.I.) remained until recent years as a punishment for boys. Birching was suspended in the service in 1906, but caning is still administered occasionally as a punishment for boys, cadets and midshipmen. “ |

|

Gravel was used as moveable ballast to adjust the balance of the ship. |

|

Both Randal and I seem to remember this overhead beam had the name of one of the sailors carved into it. |

|

I loved the wood floors. But unlike the USS Constitution there were no prisms embedded into the deck to let in light below. |

|

HMS Victory’s hardstand supports. |

|

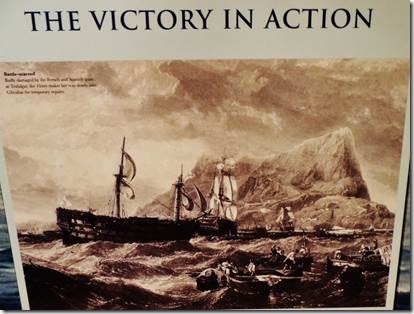

I certainly recognize “The Rock of Gibraltar” where Victory was towed after the battle of Trafalgar off the coast of Spain. |