November 22, 2014 (Coming from Massachusetts I’ll always think of November 22 as the day President Kennedy was assassinated.)

Roanoke, VA USA

Hi

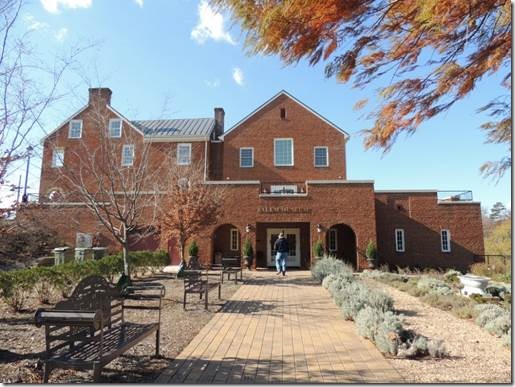

After a morning at Salem’s Lake Spring Park back in October with my friend Sarah, I learned the park’s history on the website of the Salem Museum & Historical Society. This past Thursday Randal and I finally went off to visit the actual museum. We both enjoyed the visit a great deal and will certainly return when we’re home for good!

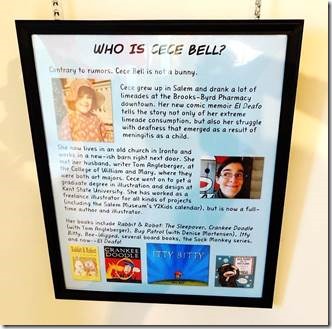

Not only is the museum a place for history, but for art as well as you’ll read below. I became fascinated so with the story of Walter Biggs and also Peter Ballard. And my niece and nephew share a teacher with Cece Bell. Mrs Eichelman.

Location: 801 East Main Street Salem, Virginia 24153 (540) 389-6760

Hours: Tuesday – Friday, 10 am to 4 pm Saturday, 10 am to 3 pm (But check for holidays or inclement weather closings. )

Admission – Free (donations gratefully accepted!)

Directions: From I-81, take exit 140 and bear right on Thompson Memorial Blvd. At Main Street (US 460) turn left. Go .3 mile; the Salem Museum is located at the top of the hill on the left.

“ Since 1970, the Salem Historical Society has been dedicated to the mission of “preserving the past, informing the future.” Located since 1992 in the Williams-Brown House (built 1845), and since 2010 in our state-of-the-art, environmentally sensitive addition, the Salem Museum is a vital part of our community. Enjoy your visit to our website and come back often–but we’d also love to welcome you in person at our Museum! “ http://www.salemmuseum.org/

|

The Williams-Brown House (L) with the new addition (R) where the entrance is located. “In a lush valley of the Blue Ridge–along what was once the “Great Road” leading westward through Virginia–sits the historic Williams-Brown House. A two-story brick home listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Brown House is typical of buildings which served travelers in the mid-19th century. Originally used for the dual purpose of a residence and post office/general store, today it is home to the Salem Museum.” http://www.salemmuseum.org/about.aspx |

|

In the museum foyer was an exhibit of student art inspired by the 2014 Art on the Way Art Show https://www.facebook.com/artontheway14 “Art on the Way is dedicated to the memory of local Salem, pioneering artist Harriett Stokes, responsible for 40 years of the successful Art in the Alley art show. She was an accomplished fine artist and considered the “grande dame of art in the valley”; most importantly, Harriett is most remembered as a passionate mentor and for giving back to the arts community with art education.” I missed attending this year’s art show but hope not to miss them in the future. |

|

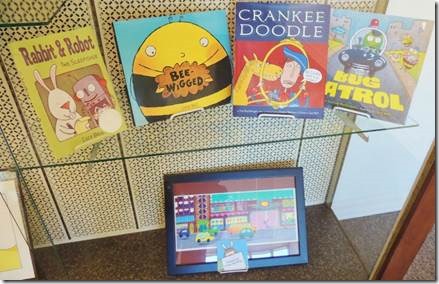

“El Deafo!” — An exhibit featuring the whimsical work of Salem-bred children’s author and artist Cece Bell. Her important new memoir about growing up in Salem with a hearing disability is generating national buzz. Book available in the museum gift shop! http://www.salemmuseum.org/cur_exhibits.aspx “I am a children’s book author and illustrator, and, quite possibly, a hermit. I eat nuts, avoid nits and gnats, and make lovely nets out of knots. My books include RABBIT & ROBOT: THE SLEEPOVER, CRANKEE DOODLE (with Tom Angleberger), BUG PATROL (with Denise Mortensen), ITTY BITTY, BEE-WIGGED, two chunky board books, the SOCK MONKEY series, and coming soon: EL DEAFO!” |

|

“Pre-Salem: What was here before 1802? — An informative exhibit highlighting what happened in our valley long before Salem began as a town in 1802. Learn more about local Native American evidence and the lives of the earliest pioneers, including General Andrew Lewis. “ |

|

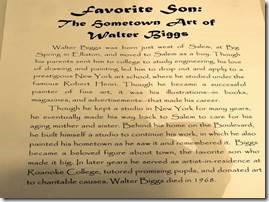

Walter Biggs Remembered: Artist Was Story Teller by Richard Persinger Richard Persinger, Salem native and graduate of Roanoke College and the University of Virginia Law School, lives in retirement in Dobbs Ferry, New York, with his wife, Mildred Emory, also a former Salem resident. These are his recollections of Salem artist Walter Biggs. Walter Biggs, 1886 – 1968, had a sufficient reputation as an illustrator and fine arts painter so that his biography has been sufficiently recorded. He was born at Elliston, Virginia, about ten miles west of Salem, Virginia, the two places being joined by U.S. Route 11. I remember traveling through Elliston, which consisted at that time of a very few houses. He came to New York in 1903 and had a studio there until after the middle 1940’s. After that he moved back to Salem where his mother and sister had lived for many years. While I lived in Salem, until I left permanently in 1939, I didn’t really know Walter, although the Biggs house was just around the corner from where I lived. Of course, like most people in town, I recognized him on the street when he came for visits about once or twice a year. He was a striking figure — tall, very thin, black hair and a neatly trimmed mustache –the epitome of an artist as a popular ideal during that time. When I moved to New York, I shared living quarters with Randy Chitwood from Roanoke, Virginia, then a much younger and less well known artist, who for some six or seven years had been studying and painting in New York. Soon after I arrived, we moved into an apartment on West 68th Street. Neither of us could afford a whole apartment. At the time my income as a law clerk, including unpaid overtime, allowed discretionary expenditures of about seventy-five cents or less a day. That included newspapers, going to a movie now and then, getting my pants pressed and everything else. Through Chitwood I immediately became a dinner regular, as part of the group eating at a Child’s restaurant located on Amsterdam Avenue, a short distance from our apartment on 68th Street. Every evening about dinnertime, from three to about seven of the group of eight or nine regulars would assemble for dinner more or less together. Almost every evening there were lots of complaints about the food, but the company was great. There were, besides the newcomer, artists, a couple who had a business or renting photos from their extensive library of pictures, a bachelor who had been an engineer, an editor of the Chicago Tribune and a highly successful author of short stories, and, of course, Walter Biggs. After two years I moved to an apartment on the East Side, but continued to see Walter from time to time. These contacts were much more frequent after the arrival of my new wife, Mildred Emory, when we were married in 1942. Walter had been a good friend of Mildred’s mother and the Emory family for many years. Besides the conversations during the extensive time I spent in Walter’s company, when I think of him my thoughts quickly go to some of the scores, if not hundreds, of stories that he told. During this period, when something reminded him of another story he would say — “I’ve probably told you about — “. This was usually accompanied by a very much raised eyebrow. He had a talent for raising an eyebrow so high on his forehead that it gave the impression of going up several inches, turning over one or two times and then falling back into place. In spite of the many stories he told, I do not think he ever repeated a story. My wife wishes I had the same record. After spending a good deal of time with Walter, I had never known that he had, you might say, been a professional baseball player. Some time before he had moved to New York, he had played for Richmond or one of the other small cities in the eastern part of Virginia. These teams were organized in the Atlantic League. He told one story of a game to decide the League Series winner for the year, a game that went into numerous overtime innings. Walter’s team scored a run and pulled ahead. If they could keep their opponents at bat from scoring another run they would win. With two out, an opposing batter hit a long drive that landed just at the perimeter fence. The nearest fielder ran toward the ball. When he got close, his spirits sank. Just where the ball landed by the fence a fence board was missing. The ball was nowhere in sight. He was desperate. Nearby he saw a potato – rather round and about the size of a baseball. He picked it up, threw it in; it was relayed to the catcher and the runner was out at home plate. Walter’s team celebrated winning the series and went home. He never told me the identity of the hero who won that game. I have sometimes wondered whether he was later a well known artist in New York. Soon after Walter came to New York he had a studio in the Lincoln Arcade, located about where Lincoln Center is now. Walter lived in his studio, where the living arrangements consisted principally of an old steel army cot. He told a story of a painting he was doing, on commission for an illustration, that included a number of human figures. He worked quite a long time on it and, as he neared completion, painted in the skin tones — hands and faces– of the figures. Then he went to sleep on his cot in the studio. Next morning, as he prepared to finish the picture, he was much disturbed to find that the hands and faces of all the many figures were completely bare — no paint, only bare, clean canvas. He was sure he had put in all the skin tones the night before. He painted in the skin tones again and in due course went to bed. Next morning, the same bare spots on the canvas, while the rest of the painting remained untouched. That night, after painting in the skin tones a third time, and after a small dinner staying at all times in sight of the painting, he turned out the lights and sat down on his cot, determined to watch the painting all night. As soon as the light was turned off and the studio was quiet, he watched by the light coming in from the street, many large croton bugs came out of the drain of the sink, rushed to the painting and started eating the fresh paint. Next day, he realized that the paint for the flesh tones had been mixed with glycerin, which those large water beetles evidently considered a great delicacy. A day or two later he delivered the painting which had been elaborately protected in the interval. My wife and I have been fortunate enough to have a number of Walter’s paintings. These were acquired by gift from Walter, purchase from him or because they were given by Walter to Mildred’s or my parents. The first one, given us as a wedding present, was a watercolor which had recently won second prize in the Chicago Watercolor Show. The scene is a small street or alley in Charleston, South Carolina, depicting the homes of some black people. Some are leaning out a front window, sitting on the front stoop, or standing in the street. Others are in the street at a distance. Like much of Walter’s work, as the picture becomes more and more familiar, the viewer continues to find more figures and build in more detail as understanding of the scene continues to grow. While we were living in New York, we suggested that if Walter had time between his other invitations he should have Thanksgiving dinner with us at our apartment. On Thanksgiving, when he arrived at the appointed hour, he pulled from his overcoat pocket a rather crumpled piece of paper, saying that we probably wouldn’t want it. It was a watercolor of the old slave market in Charleston, long since demolished, painted from sketch notes which he had made by moonlight some years earlier. Of course, we have always treasured this painting and it has always hung on our wall. Walter never dressed like a modern hippie artist. Always, when I saw him on the sidewalks of Salem long ago and when I knew him in New York, he was carefully dressed — jacket, white shirt and tie — as if about to make an afternoon call on a Southern lady. I never saw him in a painter’s smock or paint-covered work pants. Typically he bought very fine tweed suits and topcoats. He did seem to wear them rather a long time, but if the material might lose a little of its body, the garments still retained the distinctive look of fine clothes. On occasion he might drop a little paint — sometimes oil paint — on his suit. His practice was to let it dry and then scrape it off the fabric with a very sharp knife. The good quality fabric seemed to tolerate this treatment quite well. Walter’s habit of rather careful dressing did not carry over to neatness in his studio. It appeared that when he finished painting for the day he just quit. On his palette there might be gobs of paint of many colors, open and broken tubes of paint lying about, a few discarded brushes and other debris of the work day. In his studio there was a long-unused fireplace in which were sitting a large number of crockery containers in which were stored what appeared to be literally thousands of used brushes, caked with paint. The high ceiling studio had a large balcony across one end which was filled with trunks, boxes and piles of costumes of all kinds. When he needed a costume for a model he could usually search through the inventory stores on the balcony and find what he needed. He might need an elegant outfit for a gentleman of the days of the three musketeers. It would probably look very bedraggled after years of haphazard storage, but under Walter’s hand guided by his artistic eye it would come out as very elegant indeed. Walter solved many of life’s problems by ignoring them. Usually this seemed to work out fairly well. After I had seen a number of photographs of the interior of the homes of black people living in the country, some of them showing the kitchen area with the wood fired cook stove, I asked him how he had gotten such good pictures with such limited light. These had been taken around or soon after 1900. It was often difficult to take good time exposures with the camera equipment of that period. Walter said he had just snapped them with a box camera that someone had given his sister, Lucy. However long Walter worked on a painting, he was never satisfied that it was finished; that it was the best that it could be. For many years he provided illustrations for stories in the Ladies Home Journal. He was nearly always late for due dates. On one occasion, he painted nine different versions of an illustration for a story scheduled for publication. Finally, after about a year of delay, the frustrated editor called Walter and said he had to have the illustration. Faced with this ultimatum, Walter looked over his nine attempts and selected number two, which he shipped off to be used. Usually late in finishing his illustrations, Walter had a regular method of making these last minute deliveries. There was no Federal Express or other guaranteed overnight mail. He would wrap a piece of paper around the canvas, take it down to Pennsylvania Railroad Station at 34th Street, give it to a porter on the club car, hand him a dollar and ask him to give it to a messenger from the publisher who would meet the train. Then he would call the publisher in Philadelphia and report that the picture was on the way and should be picked up. This form of special delivery seemed always to be successful. For a while Walter was involved in an arrangement, which I am sure was unintentional, , that took out of his hands to a large extent the decision as to when a painting was finished. A young woman opened an art gallery on the street floor of West 67th Street where Walter had his studio and living quarters. She very much admired Walter’s work and was eager to have as much of it as possible in her gallery. She visited his studio frequently and watched closely as he worked. When she decided that a painting was finished, she snatched it away, let the paint dry and put it on exhibition in her gallery — with Walter protesting that it was not finished. This system seemed to work out rather well for a while. I do not know the reason that it was discontinued. Probably Walter did not like anyone organizing him or interfering with the way he did his work. http://www.salemmuseum.org/guide_archives/HSV3N1.aspx#wbiggs Watercolor http://www.arcadja.com/auctions/en/biggs_walter/artist/81866/ |

|

Courtesy Salem Museum and Historical Society “War News” is part of the Salem Museum’s exhibit titled “Favorite Son: The Hometown Art of Walter Biggs,” which includes about 10 paintings. The painting, which depicts an anxious-looking black family gathered in front of their house while a boy plays with a toy gun, won a gold medal from the American Watercolor Society in 1951.” http://www.roanoke.com/arts_and_entertainment/columns_and_blogs/columns/arts_and_extras/arts-extras-salem-artist-walter-biggs-commemorated-with-marker/article_31d9da6c-fd75-11e3-a9b3-001a4bcf6878.html |

|

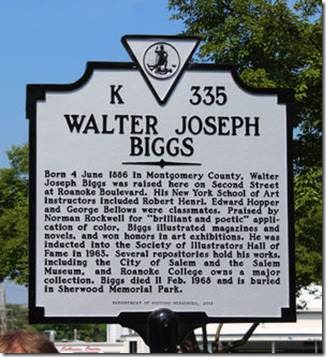

Photo from Roanoke.com “The city of Salem’s pride in its most famous artistic resident gained a permanent monument this week, with an official Virginia historical marker dedicated at the intersection of Roanoke Boulevard and College Street, across from Biggs’ family home. The city, the college and the Salem Museum and Historical Society split the cost of the $1,500 marker, said museum director John Long……” “Though the Salem Museum’s most popular exhibition remains its retrospective on Lakeside Amusement Park, the Biggs exhibit draws visitors, too — mostly locals.” Full article link below |

|

Lakeside Amusement Park display “In In the hot summer of 1920, a mammoth swimming pool named Lakeside opened just east of Salem. Soon the resort added a Thriller (roller coaster), Twirl-Around (Ferris wheel), and other rides until Lakeside became the destination for summer fun in western Virginia. From 1968 until the park’s demise in the mid-80s, the centerpiece of Lakeside was the Shooting Star, a wooden roller coaster that at the time was the fastest in the world. Photographs, souvenirs, a scale model of the Shooting Star, and a million fond memories tell the exhilarating history of Lakeside’s sixty summers.” http://www.salemmuseum.org/cur_exhibits.aspx “Before the rides came one heck of a pool. In 1919, a group of investors led by Robert Lee Lynn and H. E. Hogan purchased the orchard of John Bower for the purpose of operating a “general pleasure resort” known as Lakeside. The name referred to the 2 million gallon swimming pool, complete with sandy beach, that they soon built. Lakeside’s swimming pool was described by the Salem Times Register a few days after opening: “The lake is 300 feet in length and 125 feet wide, with a maximum depth of 8 feet. A space of 40 by 125 feet has been provided for children, and ranges in depth from 2 to 4 feet. The Lake is surrounded by a sand beach along which a numerous benches. . . and thousands of electric lights illuminate the entire grounds. The pump used in furnishing the lake with water has a capacity of 20,000 gallons per hour. . . In the pavilion will be found cloak rooms for both men and women, a soda fountain, a newsstand, and also restaurant service. The bath houses are equipped with individual dressing rooms fitted with lockers and shower baths.” Lakeside later claimed to run the world’s largest swimming pool.”………. “Lakeside became a center of controversy in the 20s when local Judge W. W. Moffett decreed that the pool opening to “half naked” swimmers on Sunday was detrimental to public morals. The local sheriff disagreed, saying that Lakeside prevented law-breaking, since skinny dipping along the creeks and Roanoke River had diminished as a result of the pool. The case went all the way to the state Supreme Court, which ruled that Lakeside could remain open on Sundays. Park manager Robert Lynn (also president of Heironimus) soon closed the park on Sundays anyway, claiming that he had proven his point but didn’t want to offend anyone.” …….. “The center piece of the new Lakeside was an immense new roller coaster, the Shooting Star, replacing the old 1920s Thriller. At a cost of some $225,000 and a length of 4,120 feet, the Shooting Star claimed to be the world’s fastest roller coaster when it took its first ride in 1968. The Shooting Star was designed by the legendary John Allen of the Philadelphia Toboggan Coaster Company, who has been credited with a renaissance of wooden coaster development in the 60s and 70s, designing 19 coasters in 20 years. According to design specs, the Shooting Star was 84 feet tall and 4,120 feet long. It took approximately 120 seconds for loading, running on track, and unloading in the station. It had two trains (red and blue) consisting of four cars per train, and carrying six passengers per car (24 passengers per train). The coaster required 320,000 board feet of lumber, 19,000 lbs. of steel, 1,600 gallons of paint, 7,000 lbs. of nails, 14,000 lbs. of bolts, and 600 feet of lift chain powered by a Westinghouse 100 horsepower motor.” http://www.salemmuseum.org/lakeside.aspx |

|

Once upon a time many of these portraits hung in the small conference room at the Roanoke County Public Library HQ branch where I worked for 26 years. I think Mr. Garretson, my first library director had agreed to house them at some point. I found them rather daunting. I think many of them were Confederate soldiers which, for me, a “forever New Englander” was ….. We had monthly staff meetings as well as book buying sessions in the room. So I saw the portraits a lot! “History in Oak Frames: The Courthouse Portraits of 1910– for the new Roanoke County Courthouse in 1910, a local judge commissioned the creation of one of Virginia’s finest collections of historical portraiture. Come learn more about these local notables!” |

|

“The Fashion Dolls of Pete Ballard: West Virginia artist and fashion historian Pete Ballard created these lovely ladies especially for the Salem Museum, to highlight women’s fashions in bygone days. “ http://www.salemmuseum.org/cur_exhibits.aspx In his conservation efforts, Ballard went through vast amounts of fabric and would have many leftover scraps when the projects ended. “Over the years, I realized the scraps were getting finer and rarer,” Ballard said. At the point I decided I was no longer interested in museum work, I found I was stuck with a mountain of fine scraps.” These scraps launched him on his next career, creating fashion dolls, which he dressed in researched authentic period costumes. Ballard’s fashion dolls are now known across the United States. Like most of his art, the hundreds of dolls he has produced have been donated. “I do not make money producing my art. I donate it,” he said. http://www.wvculture.org/agency/press/ballard.html I was captivated by their marionette-like hands and stylized faces… http://www.wonderfulwv.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/Archive/Dec2013.pdf is a 6 page interview with a very fascinating Mr. Ballard. |

|

Looking out at Longwood Park and the mountains behind…maybe Little Brushy Mountain! |

We didn’t stay nearly long enough, but it was a great first visit. The volunteer at the desk was very helpful as was Museum Director Richard Long. I think when we return to Roanoke permanently it might be a great place to volunteer!

Current Exhibits at The Salem Museum & Historical Society…..

“El Deafo!” — An exhibit featuring the whimsical work of Salem-bred children’s author and artist Cece Bell. Her important new memoir about growing up in Salem with a hearing disability is generating national buzz. Book available in the museum gift shop!

The Brand Collection: Aboriginal Artifacts from across the Globe A collection of exotic pieces from Third World cultures, reflecting the travels and tastes of Cabell and Shirley Brand, two of Salem’s leading citizens.

Favorite Son: The Hometown Art of Walter Biggs: The best known artist from the Roanoke Valley

was famed illustrator and Salem native Walter Biggs. His worked graced many a national magazine,

advertisement, and book, and his local scenes are especially prized today in his hometown.

The Fashion Dolls of Pete Ballard: West Virginia artist and fashion historian Pete Ballard created these

lovely ladies especially for the Salem Museum, to highlight women’s fashions in bygone days.

History of Salem exhibit

Salem’s Attic: Amazing Artifacts from our Archive– an exhibit of some of the really cool stuff from the Salem Museum collection

History in Oak Frames: The Courthouse Portraits of 1910— for the new Roanoke County Courthouse in 1910, a local judge commissioned the creation of one of Virginia’s finest collections of historical portraiture. Come learn more about these local notables!

The Fiery Ordeal Through Which They Passed: Salem and the Civil War— an exhibition commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the American Civil War, this exhibit chronicles the surprisingly active role Salem and Roanoke County played in the war, as well as how it has been remembered through the years.

Pre-Salem: What was here before 1802? — An informative exhibit highlighting what happened in our valley long before Salem began as a town in 1802. Learn more about local Native American evidence and the lives of the earliest pioneers, including General Andrew Lewis.

http://www.salemmuseum.org/cur_exhibits.aspx

Exhibit Opening When: Thu Dec 4, 2014 – Paint & Pieces: An Exhibit of Mixed Media by Pam Odgen & Quilts by Mary Ed Williams Runs through the end of January.