Hi All,

I visited Sarah Cohen yesterday and the Cochin Synagogue today. Randal stayed on the boat and supervised some men who were washing the pounds of salt from DoraMac.

Ru

DoraMac

Cochin Synagogue Jew Town

The Synagogue is located at one end of Jew Town Road.

First we went Friday morning and then, today, I planned to go after lunch at 1 pm.

Randal returned to the boat but I walked around the shops of Jew Town and endured “come into my shop…just look…looking costs nothing…” And it did cost nothing because, as charming and smiling and willing to make a deal they all were, I didn’t buy anything. Telling them that I lived on a boat sort of threw them off their game a bit. I knew the Synagogue sold booklets and such and wanted to save my money for those things and also for a return visit to the Idiom Book Store on my way back to the boat yard.

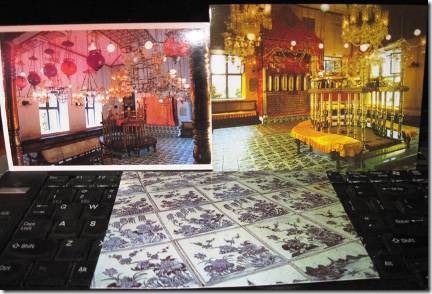

Postcard were sold at the Cochin Synagogue but photos were prohibited.

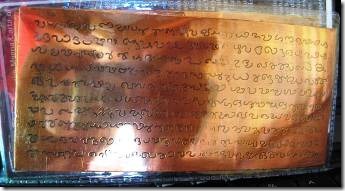

VB Anand, Richard Todd, and anonymous get credit for the photos. I was going to show each card separately but there are copyright notices on the Anand and Todd cards so I have reservations about posting them at all. When I visited the Synagogue looked like the card on the left with the pink curtain across the ark and no Torahs visible. There were about 50 or so school children there when I was there and they were told all about the Synagogue in Malayalam, the local language. There was no English translation for the rest of us. A few small groups were there with their own guides but I didn’t feel right listening in so I didn’t. This is what the India Map Service Tour Guide has to say… ” It was built in 1568 and is the oldest synagogue in India. The synagogue was partially destroyed during the Portuguese raids in 1662 and was rebuilt by the Dutch. The clock-tower was later added to the structure in the mid-18th century and the floors were paved with the exquisite hand-painted blue willow tiles from China. The Great Scrolls of the Old Testament, the copper plates depicting the grants of privilege made by the Kochi rulers, Hebrew inscriptions on stone slabs and other ancient artifacts are some of the evidence of the Jewish history stored here. The township around the Synagogue is known for spice trade and curio shops dealing in antiques as well as rare glass and beads. “

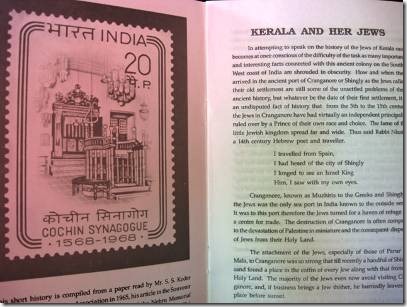

Kerala and her Jews, a small booklet sold at the Cochin Synagogue

Jews may have been in Kerala since the time of King Solomon.

Replica copper plates of the grant giving tax privileges, many rights and the area now Jew Town to Joseph Rabban and his descendants by His Majesty the King Sri Parkaran Iravi Vanmar in either the 11th century or 379 according to the Cochin Jews.

The clock tower was built in 1760 by Ezekiel Rahabi who had also donated the blue and white Canton tiles.

So tiring to visit those shops.

I grew up in New Bedford where you went into a shop, looked around, were left mostly alone, picked what you wanted, paid and walked out without a whole lot of interaction between seller and buyer. In the South, clerks chat and if you don’t chat back you’re thought to be a bit rude. One of the attractions of working in the library, money wasn’t part of the transaction: at least it wasn’t when I worked there and the library wasn’t so broke. You were expected to chat with the patrons and I mostly enjoyed that because they were friendly and had really interesting stories to tell. I truly don’t enjoy wheeling and dealing or bargaining. Give me a fair price and let me pay it. I have no clue what something is worth where labor is cheap. I only know what I would pay at home which I am told means nothing but what else can I compare it to. While cruising I buy lots of inexpensive tops, so there I have an idea, but not other things. And when shops are so empty, I feel awful not buying when the sales guys are so charming and sad. But they are all charming and all sad and there are shops all along and they all sell the same things. And for the most part you can buy the same things everywhere in the world.

Jew Town shops.

Jew Town as tourist destination.

Several cruise ships are visiting Cochin. Tour groups are brought to our neighborhood to visit the Chinese fishing nets and to visit Jew Town. Here the tour guide is holding up a post card of the Synagogue as he is about to lead the group into Sarah Cohen’s hand embroidery shop and home.

89 year old Sarah Cohen and me in one of my Sri Lanka blouse lady tops and my old Red Sox hat.

Sarah does hand embroidery

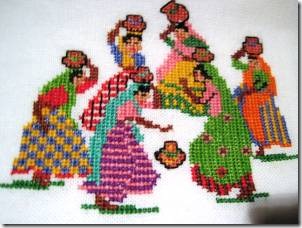

I bought a hand towel with this image of Indian women. Even the back looked lovely.

www.sarahshandembroidery.blogspot.com is her web site

Brothers Thaha and Abdul, long-time family friends, comes daily to check on Sarah and help her with her shop.

Sarah had lots of visitors

“All the Cochin Jews moved to Israel…why not you?”

This German born Israeli woman wanted to know why Sarah hadn’t emigrated to Israel. I was so offended by her incredulity that Sarah would want to stay in India, that I butted in and said, “because she likes it here in Cochin.” That actually was the answer and the woman from Israel and I had an interesting discussion about why I feel about America as she does about Israel.

These women came with best wishes from Sarah’s Cohen cousins in (I forget where) and Sarah’s response was that she had no cousins there. The ladies kept insisting and Sarah kept insisting. While they were discussing, Thaha offered to show me the rest of Sarah’s house parts of which are 300 years old.

Sarah’s wedding photo, she is now a widow.

Sarah’s husband was a lawyer. They had no children she told the Israeli woman, but her sister had six.

Sarah and friends playing cards.

Sarah in traditional sari as Cochin Jews added Indian customs to their daily lives.

Sarah was born in Cochin: her parents came from Baghdad.

Sarah’s room, simple but very cool and that’s most important in tropical India.

Abdul, Sarah, Thaha

Both brothers help take care of Sarah. I met Abdul during my second visit to Sarah.

I left Sarah’s house and felt as if I were saying good-bye to relatives. I was quite taken by her and Abdul. I’m going to try to make time to return before we leave Cochin. I don’t know if Sarah will remember me, her memory is fading a bit, but that’s ok. I’ll remember her and Abdul. I found the two following articles on the Internet. They tell not only about Sarah but illustrate Jewish life in Cochin where Jewish and Indian customs became mixed.

http://www.mathrubhumi.com/english/story.php?id=101523

Kerala Jews come to relive past, as present fades

Posted on: 02 Dec 2010

Kochi: From thousands, the number of Jews in Kerala has dwindled to a mere 10 and they too live only in Kochi. The exodus of the community started over 60 years ago, though many visit this city to discover their roots and relive the past.

Sarah Cohen, 89, the oldest Jewish woman here who became a widow a decade back, talks wistfully about the fast dwindling numbers of the community – just five Jew families reside here now.

‘Our community members started leaving here right from the time Israel was formed in 1948. All my sisters and brothers left long back. I don’t have children but decided that I won’t leave this place because I have been born and brought up here,’ Cohen told IANS.

‘Of course, most of those who left do come back and visit us frequently to relive their past, because for them it is a discovery of their roots,’ she said.

But things are pretty difficult for the community.

‘Today, the situation is such that the weekly Sabbath (prayers in the synagogue) takes place only if Jews from outside are visiting,’ Cohen said.

‘According to rule, 10 (Assara) men have to be present in the synagogue. But only six women and four men are left in the Jew Town in Kochi,’ said Cohen, who lives in a 300-year-old home built by her ancestors.

The Jews are classified into two categories which have been there since their arrival here – ‘white Jews’, who are descendants of traders, and ‘black Jews’, who the fairer complexioned say are the descendants of slaves.

The ancestors of ‘white Jews’ came from Europe and Baghdad, it is said. And even today, white Jews do not allow their daughters to marry into the darker families.

Joy, a 47-year-old caretaker of the Paradeshi Synagogue for the past two decades, said the ‘black Jews’ live away from Jew Town and till recently they were not welcomed by the ‘white Jews’ into their Paradeshi Synagogue.

‘To have the Sabbath, the ‘black Jews’ now at times come over to this synagogue to make up the number of 10 men. They are also a mere eight in total,’ he said.

Recently, the happiness of many Jews knew no bounds when they got a new rabbi (religious teacher of Judaism).

‘Those who know Jewish traditions know how orthodox we are when it comes to prayers. We are lucky because some Jews living in America were kind enough to send us a new rabbi who now lives permanently in Kochi,’ Cohen said.

‘But with 10 Jewish men living permanently here not being always available, our Sabbath takes place only if we have visiting Jews. Last week on two days we had our Sabbath because 20 Jews came on a visit tracing their roots,’ she added.

According to Jewish customs, they don’t eat meat and fish from other homes.

The availability of ‘Kosher meat’, according to Jewish guidelines, is now impossible because there is none who knows how to slaughter animals that chew cud and have cloven hooves.

‘We are so orthodox that even our new rabbi does not eat from my home, so you can gauge how orthodox we are,’ said Cohen.

With the Jewish population dwindling, all eyes are on what would happen to the Paradeshi Synagogue – the oldest synagogue in the Commonwealth nations – that was built in 1568 by the Malabar Yehudan people or Cochin Jewish community in the Kingdom of Cochin.

‘Barring every Friday and Saturday, it is open for visitors who come in large numbers to see the building. On Fridays and Saturdays, it is out of bounds for all and only Jews are allowed inside to conduct their prayers if they have the required numbers,’ Joy said.

Asked what would happen to the synagogue a few years from now, Cohen’s answer was quick: ‘Your guess is as good as mine!’

In India, a Jewish Outpost Slowly WithersAfter Many Emigrated to Israel, Once-Thriving Community on Southern Coast ‘Is Dying Out’

By Emily Wax

Washington Post Foreign Service

Monday, August 27, 2007

KOCHI, India — Down a narrow, stone-paved road in a quarter known here as "Jew Town," a woman with salt-and-pepper hair was sewing glittery beads onto the rim of a Jewish prayer cap. It was just after 3 p.m., and Sarah Cohen, wearing a housedress and flip-flops, sat in the sunny doorway of her shop, waiting for the visitors from around the world to come in for a visit.

Cohen lives right near the Pardesi Synagogue, which was built in 1568 when Jewish spice traders set up businesses in this small outpost of the Jewish world on the South Indian Malabar coast. The synagogue

sparkles with colorful Indian chandeliers and green and red glass candleholders that swing from the ceiling beams. The floor is intricately patterned with blue and white tiles imported from a Jewish community in China in the 15th century.

As visitors wandered by on their way to the synagogue, one of the oldest in the world, they looked curiously at the little Jewish woman speaking in Malayalam, the language of the southern state of Kerala.

Cohen explained that she is a part of a dying tradition here that will probably no longer exist in 10 years, because most of the Jews who used to live here emigrated to Israel during its creation in 1948. Now, there are believed to be only 13 elderly Indian-born Jews — from seven families — still living in Kochi, a sun-dappled city thick with coconut palms.

"We couldn’t bring ourselves to leave. We are Indians, too. Why should we leave the only place we have known as home?" Cohen said with a gentle wobble of her head, an Indian gesture sometimes used for emphasis. "Besides, I like this place. And I like the people."

Jews flourished in India for centuries — from biblical times, some scholars say. The country also gave safe haven to Jews during World War II.

Small but active Jewish communities remain in Mumbai, including the so-called Baghdadi Jews who come from Iraq, Iran, Syria and Afghanistan and are thought to have arrived about 250 years ago. In northeastern India, an estimated 9,000 Indians started practicing Judaism in the 1970s, saying they were a lost tribe and descendants of the tribe of Manasseh. Israel has recognized them as ethnically Jewish.

But in Kochi, there is concern that Jew Town soon will be little more than a quirky tourist destination.

On a recent afternoon, Cohen’s friend Abdul Anas, 33, stopped by to check on her. He often looks in on her, since he was good friends with her husband, Jacob Cohen, a lawyer who died eight years ago.

Sarah Cohen and Anas spoke easily to each other in Malayalam. They laughed when Anas said that he was a Muslim but didn’t mind working in Jew Town. They don’t discuss Israel or politics, they said. "Who cares?" Sarah asked. "That’s over there, and we are here," Anas shrugged.

"To me, it’s a part of Indian history. Her husband always gave me fair work. I call her auntie. And she’s alone now so I take her to the hospital when she is sick," said Anas, who sells postcards of the synagogue from his pushcart. "I feel bad for her. And actually I feel really sad that the community is dying out."

Israeli tourists to India, along with Jews from the United States, sometimes drop off boxes of matzoh ball soup mix and kosher cookies. "They tell me I remind them of their bubby," Cohen said, using the Yiddish word for grandmother.

Cohen displayed her frilly white bread covers, used on the Jewish Sabbath during a blessing over the bread. The covers were stamped with her name: "Sarah Cohen: Kochi, India."

"We are kosher, but also Indian," she said, adding that she uses chapati, an Indian flatbread, rather than the braided challah bread of European Jews.

The Jewish community here eats no beef, out of respect for the Hindu prohibition on eating cow meat. But they do keep kosher, eating chicken cooked with cloves, chickpeas and cardamom and fish curry steeped in coconut milk along with pineapple and mango for dessert, Cohen said. "Why not? Fruit is kosher."

She shuffled into her small living quarters next to her shop for some ginger tea and cookies.

Outside, some tourists were lining up to visit the synagogue. In Kerala, there are still three synagogues, but the one here is the only one still open and is a protected heritage site.

A series of large oil paintings in an entry room of the synagogue tell the history of the Jews in Kochi. The first painting depicts King Solomon’s merchant ship greeting Indian leaders and trading peacocks, ivory, spices and teak wood.

The inscriptions under the paintings say that the Book of Esther in the Old Testament contains the first written mention of Jews in India. The Jews blended many of their customs with their host country’s. For instance, a dialect called Judeo-Malayalam, a mix of Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam and Hebrew, was spoken. In Kochi, shoes are taken off before entering the main prayer room, as in Hindu tradition, and flowers are used as a part of prayer.

K.J. Joy, the Hindu caretaker of the synagogue for 25 years, said it’s only a matter of a short time before the Jews of Kochi disappear, and with them the unique mix of Indian and Jewish culture. "This will become a monument, not a working synagogue," he said. "For that, we feel really horrible."

He showed a visitor a small pamphlet written by members of the community in the 1980s, which tells the history of Jew Town. The booklet praises India for giving shelter and respect to the Jews throughout history.

"After some years the story of the Jews of Malabar may come to an end," reads the small book handed out to visitors for 10 rupees, or about 20 cents. "If this happens, history can record that their emigration was not motivated by intolerance or discrimination by India."

View all comments that have been posted about this article.

© 2007 The Washington Post Company

![clip_image001[1] clip_image001[1]](http://www.mydoramac.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/clip-image0011-thumb.jpg)

![clip_image001[3] clip_image001[3]](http://www.mydoramac.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/clip-image0013-thumb.jpg)