Merhaba/Shalom,

I thought I’d never get this email finished. I certainly wish I had a library handy to make research easier. This email goes on forever, and it’s about one small part of the Old City of Jerusalem. But I found it fascinating. It was quiet and away from all the hustle and bustle. I wish I’d had more time. Wish I’d taken the time to pay more attention to the handout while I was there so I would have better photos for you to match what you read. Oh well, to quote my pal Joesephine, "done is better than good."

Ru

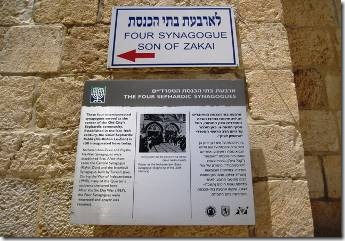

I don’t know why I decided to visit the Four Synagogues. I almost didn’t because the door looked closed. And since I’m really non-observant, I almost feel as if I’m intruding. But the kind man working at the desk that day, covering for his friend who regularly sits there, made me feel welcomed. When I was confused about which synagogue was which, he walked with me matching the information from the hand-out to where I was actually standing. I don’t have his photo as he didn’t want to pose. He was, after all just covering for his friend. Of course what made sense while he was showing me made no sense when I started writing this email. I hope I have them correct.

“According to the Talmud, as Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai was coming out of Jerusalem after the destruction of the Temple, he stated, "…be not grieved, for we have another means of atonement which is as effective, and that is the practice of loving-kindness, as it is said, For I desire goodness, not sacrifice (Hos. 6:6)".The basic philosophy of Judaism in all of its forms today can be traced back to this one great Rabbi.” http://www.jpost.com/Travel/AroundIsrael/Article.aspx?id=252353

Here is a map of the 4 Synagogues that I stoel from the website you see near it…in case it disappears when I send the email.

http://www.jewish-quarter.org.il/atar-bksf.asp

http://www.jewish-quarter.org.il/atar-bksf.asp

This website has lots of good info about the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem.

I went to the pink one first (Yokhanan ben Zakai); the orange one second (Emtza’I Middle Synagogue); the darker blue third (Istambuli); and then the greenish one last (Eliahu Hanavi .) It wasn’t the order of the hand-out so I got a bit mixed up and looking at Wikipedia just made it worse. But I think I have it right now. One of the things my “tour guide” told me was that one of the synagogues was actually originally an Ashkenazi Synagogue. But I can’t prove that to myself, so I don’t know.

This is the handout I was given….and didn’t take the time to read thoroughly as it was long and I was tired and it was getting late. I have repeated the parts about each synagogue with the photos of that synagogue so you don’t have to scroll back and forth.

FOUR ANCIENT SYNAGOGUES – THE BEATING HEART OF THE SEPHARDI COMMUNITY IN JERUSALEM

It was in 1267 that Rabbi Moshe Ben-Nakhman (known as Nachmanides or by his initial, as the RaMBaN) arrived in Jerusalem from Gerona in Catalonia, Spain, to bring new life and organization to the city’s Jews. He quickly set up a synagogue in a “half-ruined house with marble pillars and a fine dome” (as he wrote to his son, Nakhman)and for centuries after it continued to serve all the city’s Jews, whatever community they owed allegiances to. Until that is, in 1586 the Turkish city governor (known as Abu Seifin) ordered it closed, on the pretext that a hundred years before the building had been sanctified as a mosque. Jerusalem’s Jews had no choice but to manage again as separate communities. The Sephardim built their new center to the south of the RaMBaN synagogue, at a spot where tradition say, in the time of the Second Temple, had stood the study house of no less then Rabban Yokhanan be-Zakai himself, the renowned tanna (scholar-judge) who took over leadership of the people after the Temple’s destruction and the uprooting of the Sanhedrin from Jerusalem to Yavneh.

The need to build new synagogues coincided with a marked growth in the numbers of Jews in the city, for the rulers of the Ottoman empire allowed Jews who had settled in their territory after the expulsion from Spain (1492) to move freely within the empire and when the Ottomans captured Jerusalem in December, 1516, a steady influx of their Jews into the city had begun. However, under the prohibitions decreed by Islam, no “infidel” prayer house could stand higher than a neighboring Muslim holy place. Jews got round the difficulty by starting their synagogues’ ground floors 3 meters below street level, adorning the necessity by quoting Psalm 130, “Out of the depths, O Lord, I call you.”

By the beginning of the 19th Century the four synagogues were derelict and tottering, with the rain dripping through holes and cracks. At last, in 1835, the Sephardi community’s notables succeeded in obtaining from the Governor of the Holy Land, Ibrahim Pasha (son of Muhammad Ali, the famous governor of Egypt who had conquered the land in 1831) a permit for the synagogues’ renovation and repair. The lay-out of the areas containing the four synagogues was at the same time reshaped to make it a single compound, which now encompassed- because of the different periods of synagogue construction – a uniquely rich variety of architectural styles and features.

This period of physical reconstruction also marked a turning point in the status of the Jewish community in Palestine-Eretz Yisrael. In 1840 the Ottoman authorities restored their direct rule over the land. In consequence of this and of other changes that had taken place (for instance, the great European powers had began asserting their interests by opening foreign consulates in Jerusalem), Istanbul made Jerusalem an independent Sanjaq (district), answering directly to Istanbul and not, as before, to the governor of Damascus, and as a result, the standing of the community and its notables underwent a very positive change. Jerusalem’s Chief Rabbi, a Sephardi, who had hitherto borne the traditional Jewish title of “First in Zion” (Rishon LeTzion) was now officially designated Hakham Bashi, that is, head of the Jerusalem Jewish community and all its rabbis, and as such enjoyed official status under the Ottoman system of government.

The four, now structurally linked, synagogues, together with their study houses and charitable institutions (Bet HaRashal, the Sephardi Talmud Torah (study house), the Tifferet Yerushalayim yeshiva, the widows’ alms-house) now made up the center of the Jerusalem Sephardi community’s spiritual and cultural life, a community which until the 1870s was by far the largest Jewish community in the city and the only one to enjoy official recognition by the authorities and the non-Jewish population throughout the whole period of Ottoman rule.

The Qahal Qadosh Gadol (Great Congregation) Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai

This synagogue, built in the late 16th – early 17th Centuries, held pride of place among the four synagogue, to the extent that the whole compound was sometimes called the Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai compound. The synagogue, oriented west-east, had an elongated interior leading up to not one but two Holy Arks, both with Gothic-style fronts and symmetrically placed against the eastern wall. The high stone-built prayer dais (bima) in the center was also elongated, with a decorative wrought-iron railing on all four sides. It was in this synagogue that, from 1893 on, the Rishon LeTzion and Kakham Bashi, was ceremonially “enthroned” and where public meetings and assemblies were held and where important communal events such as the official ceremony in 1870 to welcome Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary, took place.

Until the destruction of 1948, the congregation cherished an old shofar (ram’s horn trumpet) and oil jug in a niche in one of the synagogue walls. Tradition whispered from generation to generation that with this very shofar the prophet Elijah would announce the coming of the Messiah and with oil poured from this ancient juglet the Messiah would be anointed.

The Eliahu HaNavi Talmud Torah Congregation

Expert opinion is that this synagogue (it also served as a study house) was the first of the four built. The ceiling of the main prayer hall was domed in the Turkish style and its large stone prayer dais was railed and furnished in wood. In the north-west corner is a large alcove, from which steps lead down to “Elijah’s Cave”. There people came to place lighted oil lamps , each flame imploring the Prophet to make a special wish come true.

How did the synagogue come to be named after the great Elijah? Well, the time-honored story goes that the community of Jews in the city was once so small they could not even make up a minyan (the 10 men required for holding public prayer). This was very distressing to the 9 available men, and even more so when the holiest day of the year, the Day of Atonement, arrived. There they were and the time had come to say the Kol Nidrei prayer that opens the Day, when an old man joined them and, wonderfully, made himself one of them. Then, with the day’s closing prayer, he vanished. Only then did the 9 realize that the Prophet Elijah, himself no less, had made himself one of them. To commemorate the miracle they added the name of the Prophet to the name of the synagogue.

The Istanbuli Synagogue

This synagogue is both the largest and last to be built, having been constructed in the 1760s by immigrants from Istanbul; hence its name. Its windows are very distinctive, being large and deeply recessed in the thick walls, each one made up of three long vertical panes surmounted by a single, wide horizontal one. Flanking the Holy Ark stood two Corinthian columns carved around with arabesques. Like the other four synagogues, it had a high prayer dais. The Istanbuli also had a geniza, a space or chamber where books of scripture, too worn or damaged for use but too holy to be thrown out or destroyed, were stored. Every so often the geniza was emptied and the old books and scrolls carried in public procession to be reverently buried in a cave in the ancient Sambuski Sephardi cemetery at the foot of Mount Zion.

The Emtza’I (Middle) Synagogue Zion Congregation

This is the smallest of the four synagogues called the “middle” one for the simple reason that it was built on a plot of land between the other three, a plot which apparently had, till then, been an outside courtyard of the Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai Synagogue, accommodating its women’s enclosure. The origin of the synagogue’s official name, Zion Congregation, goes back to a tradition that an underground passage once connected the synagogue to the grave-site of the kings of the House of David. Like the Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai synagogue, it has an elongated interior and a groin-vaulted ceiling.

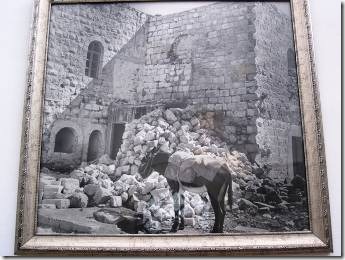

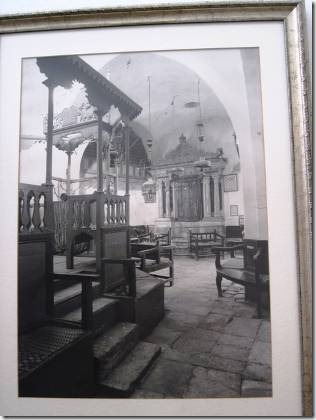

During Israel’s War of Independence (1947-48), all four synagogues provided shelter to the inhabitants of the Old City’s Jewish Quarter, and with the fall of the Old City, it was from them that the Quarter’s defenders filed out to captivity in Jordan. All four were then devastated: they were plundered, burnt and the skeletal remains used as stalls for horses, goats and sheep.

On the liberation of the Old City in 1967 Six Day War, the four synagogues were found in the ruinous state described earlier, and piled high with rubble and manure. But to our great fortune at least the outer walls stood intact. The Council of Sephardi Communities and the Jerusalem Fund, with assistance from the Israeli government, the Yad Avei HaYishuv organization and donations from other funds and individuals in Israel and around the world, took on the task of restoration. It was not until the hundreds of tons of accumulated refuse had been removed and the basic structure of walls and roof repaired and rebuilt, that it was possible to restore the structures to their former, beauty and glory.

The National Parks Authority had charge of the work, with practical direction in the hands of the architect, Dan Tannai, whose first concern at all times was to restore the original lay-out and reconstruct each synagogue’s outstanding former characteristics and features. Before the destruction, the splendor of the buildings had been their interior furnishings, especially the prayer dais and Holy Arks. Antique dais, arks and lamps were now brought from Spain and Italy and their dimensions precisely altered to fit the new settings. Item by item, the atmosphere and appearance of the synagogues of that past age was recreated.

Finally, in the intermediate days of Succot, 1972, all four synagogues were re-inaugurated and rededicated in a solemn and moving ceremony, attended by the State’s leaders and high officials.

Text by Dania Haim

http://tourguides0607.blogspot.com/2011_09_01_archive.html

Walking down the steps below street level to enter the Four Synagogues

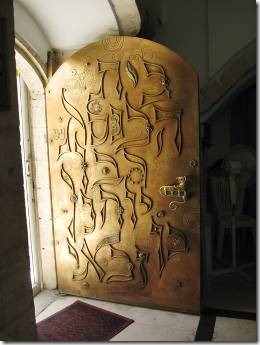

The beautiful door and the artist’s signature in the lower right corner.

Qahal Qadosh Gadol (Great Congregation) Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai

Two Holy Arks, an unusual feature in synagogues.

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com

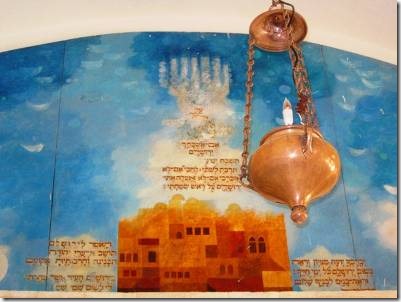

“Have a seat between the bemah (stage) and the arks at the fore of the synagogue. Notice that the bemah is in the center as is the tradition of the Spanish Jews. They believe that when the Torah is read the people of Israel should surround it and it should be held above us, in the midst of the nation. Notice the heavenly painting above the arks. The Sephardic community that returned to the Land of Israel after the Inquisition were Kabbalistic scholars and the art here represents the idea that the universe is made up of spheres, and the gap between the spheres hovered over Jerusalem. Look at the window on the south above you. There is a glass shelf with a shofar (ram’s horn) and a jug of olive oil. The tradition holds that when the Messiah comes he will be announced by the Prophet Elijah from this synagogue and this shofar and anointed king using this olive oil. It was said before 1948 that these vessels were holy and only a righteous person who had immersed himself in a mikveh (Jewish ritual bath) could touch these vessels. About fifteen years ago the synagogue’s caretaker told me that as a soldier during the Six Day War, when he entered this synagogue, which he had remembered visiting as a child, he stumbled upon a young Arab shepherd eating humus, sitting on the floor. He asked him where the jug of olive oil was and the shepherd replied that he had used it all up in his hummus! To this day I couldn’t tell if the caretaker was messing with me or not. These vessels are replicas of the originals.

The painting over the Ark.

What time I visited the Four Synagogues

Judaicia showcased in the Synagogue

Shofar and Oil Jug On one wall Tzdaka, Donations for the Poor

“Perhaps Yohannan ben Zakkai’s greatest contribution to the Jewish people lies in the Talmudic story of the destruction of the Temple. The Jewish War was raging in the year 69 C.E. and the Jewish rebels had holed themselves up on the Temple Mount. The Romans were ravaging their way through the Land of Israel, and Jerusalem was all but lost. Vespasian and his Tenth Legion would surely breakthrough to the Temple courts at any day. Yohanan ben Zakkai did what no other rabbi dared to do. In defiance of the rebels orders he knew that he must get off the Temple Mount with his disciples in order to continue the study of Torah. He played dead and his students wrapped him in a burial shroud and smuggled him out of the Temple complex, through a cemetery and straight to the camp of the Roman general Vespasian. Ben Zakkai was known to Vespasian as a man of great influence who had tried to discourage the war to no avail. He addressed Vespasian as "king" twice. As Nero was king, Vespasian believed the rabbi was just trying to butter him up, and he had Ben Zakkai locked up in the darkest of solitary confinement awaiting a death sentence. Three days later the news arrived that Nero was dead and Vespasian had indeed become king. Vespasian as a reward for his prophecy would grant the rabbi any wish. His wish was to allow the other great rabbis on the Temple Mount to join him and his disciples in Yavne, and to set up a yeshiva to keep the flame of Torah study alive, and with that he changed Judaism forever.”

Joe Yudin became a licensed tour guide in 1999. He completed his Master’s degree at the University of Haifa in the Land of Israel Studies and is currently studying toward a PhD. Joe Yudin owns Touring Israel, a company that specializes in “Lifestyle” tours of Israel.

http://www.jpost.com/Travel/AroundIsrael/Article.aspx?id=252353

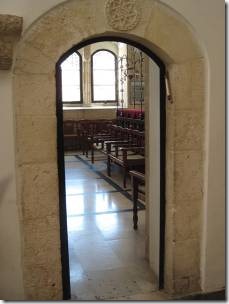

Doorway to “the Middle Synagogue”

The Ruins of the Four Synagogues

Middle Synagogue

The Emtza’I (Middle) Synagogue Zion Congregation

This is the smallest of the four synagogues called the “middle” one for the simple reason that it was built on a plot of land between the other three, a plot which apparently had, till then, been an outside courtyard of the Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai Synagogue, accommodating its women’s enclosure. The origin of the synagogue’s official name, Zion Congregation, goes back to a tradition that an underground passage once connected the synagogue to the grave-site of the kings of the House of David. Like the Rabban Yokhanan ben Zakai synagogue, it has an elongated interior and a groin-vaulted ceiling.

Istambuli Synagogue

The Istanbuli Synagogue

This synagogue is both the largest and last to be built, having been constructed in the 1760s by immigrants from Istanbul; hence its name. Its windows are very distinctive, being large and deeply recessed in the thick walls, each one made up of three long vertical panes surmounted by a single, wide horizontal one. Flanking the Holy Ark stood two Corinthian columns carved around with arabesques. Like the other four synagogues, it had a high prayer dais. The Istanbuli also had a geniza, a space or chamber where books of scripture, too worn or damaged for use but too holy to be thrown out or destroyed, were stored. Every so often the geniza was emptied and the old books and scrolls carried in public procession to be reverently buried in a cave in the ancient Sambuski Sephardi cemetery at the foot of Mount Zion.

About two hundred years after the first two synagogues in the

complex were built, Jews from Istanbul arrived in Jerusalem. This wealthy community

built a synagogue for itself, the lstambuli, alongside the two older synagogues.

When the Jewish Quarter fell in the 1948 War of Independence, all the synagogues

were vandalized. ‘With the reunification of the city in 1967, they were renovated as

part of the restoration of the Jewish Quarter. In the case of the lstambuli, the Holy

Ark you see was brought from a synagogue in Ancona, and the large “bima" or

podium from Pesaro, both in Italy.

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com

I think this is the geniza of the Istambuli Synagogue which now houses old Torahs and other documents and Judaica.

Sephardic Torah

“The Sephardim usually store Torah scrolls in a wooden box. The Torah scrolls in an Ashkenazi synagogue, in contrast, are typically covered by a mantle through the top of which protrude two staves known as atzei hayyim or "trees of life." Two finials or "rimmonim" are typically placed on top of these staves. Usually, a crown is incorporated into the design of the finials.”

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/eppp-archive/100/200/301/ic/can_digital_collections/art_context/torah.htm Canada National Archives

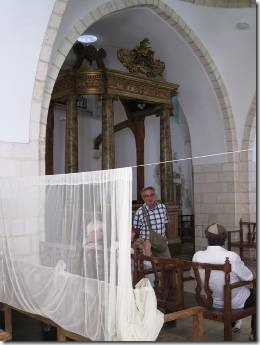

The Eliahu HaNavi Talmud Torah Congregation

Expert opinion is that this synagogue (it also served as a study house) was the first of the four built. The ceiling of the main prayer hall was domed in the Turkish style and its large stone prayer dais was railed and furnished in wood. In the north-west corner is a large alcove, from which steps lead down to “Elijah’s Cave”. There people came to place lighted oil lamps , each flame imploring the Prophet to make a special wish come true.

How did the synagogue come to be named after the great Elijah? Well, the time-honored story goes that the community of Jews in the city was once so small they could not even make up a minyan (the 10 men required for holding public prayer). This was very distressing to the 9 available men, and even more so when the holiest day of the year, the Day of Atonement, arrived. There they were and the time had come to say the Kol Nidrei prayer that opens the Day, when an old man joined them and, wonderfully, made himself one of them. Then, with the day’s closing prayer, he vanished. Only then did the 9 realize that the Prophet Elijah, himself no less, had made himself one of them. To commemorate the miracle they added the name of the Prophet to the name of the synagogue.

Note the magnificent, carved-wood holy ark, brought from a synagogue in Padua, Italy, after the Second World War. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com